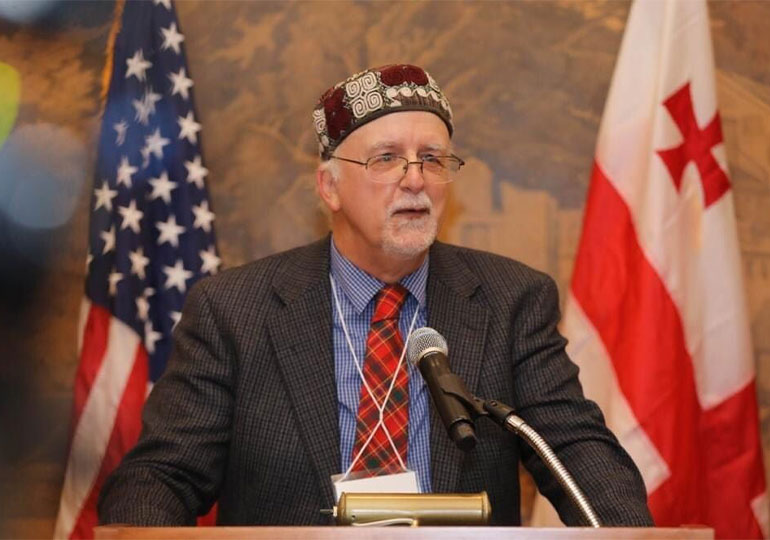

A program for Georgian Studies at Harvard’s Davis Center has recently been launched. The new program is being financed by the Georgian government through a $2.3 million grant, which will support research and scholarly exchange, teaching, and outreach. It will start in January 2022. What will this program bring to both Georgians and Americans? Forbes Georgia interviewed the head of the program, Stephen F. Jones, a professor at Mount Holyoke College and Georgia’s Ilia State University.

Harvard’s Davis Center announced a new Georgian Studies program. How did the planning and launch process go?

Six years ago, I approached my colleagues at Harvard and told them there was nothing in the United States that focuses on Georgia. The idea was to have a center where Georgian and American young scholars could come to conduct their research. It would also be a center which would inform Americans about Georgia’s political and cultural life, as well as its history. These are areas of knowledge which are underdeveloped in the US. In contrast, Armenian-Americans support a dozen chairs at various important US universities. Georgia, by contrast, is in a disadvantaged position. My Harvard colleagues, including Alexandra Vacroux, the Executive Director of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, which is part of Harvard University, were enthusiastic supporters of the idea of a Georgian Studies program. We discussed it in detail. We made two trips to Georgia in 2014, and again in 2015, if I remember correctly, to find donors who would help us fund our program. We were looking for a substantial amount of money because we wanted a good start with sufficient resources. We wanted to make a real impact.

We needed $2-3 million to get the program running. We met with a lot of millionaires and one very famous Georgian billionaire. They were all hospitable and we were hopeful, but unfortunately, it did not work out. There were not enough donors to help us. After two years of trying, it was clear to us that the project was not moving forward and the whole idea was dropped. Then four months ago, a miracle happened. I had a conversation with a colleague and historian at Ilia State University where I teach. His name was Malkhaz Toria. I recalled the disappointment of 2014-2015. Malkhaz raised the issue with Ilia Darchiashvili, who subsequently became the Chief of Staff of Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili, and the ball started rolling. The Georgian Prime Minister, and Mikheil Chkhenkeli, Georgia’s Minister of Education & Science, took a renewed interest in the project. Talks and conversations began, though I remained skeptical that it could succeed. Fortunately, both the Prime Minister and the Minister of Education and Science decided it was important, and worth pursuing. The Georgian government promised us $2.3 million for the first three and a half years. It was a dream come true, but at Harvard, we realize that we cannot depend on this money alone. We have to raise more money to continue the program after the Georgian government’s funding finishes.

What kind of cooperation do you have with the Georgian government besides the funding?

We could not have done it without Georgian government funding, and for that we are immensely grateful. Having said that, we made it clear from the beginning that we are scholars; we do independent work and promote accurate information and research. We would not tolerate any attempt to influence what we do at the Georgian Studies center. The Georgian government agreed. There will be no interference. We will no doubt be researching areas that will be uncomfortable for Georgia’s politicians, but honest and accurate information is, of course, in the best interests of Georgia.

Have you seen an increase in interest from scholars regarding Georgian studies?

Since the announcement, I have been getting hundreds of emails from people all over the world, not only my colleagues, but also other people who are both surprised and pleased that finally we have established something like this in the United States. Of course, it is a first. We have never had anything like this before, so it could be considered quite historic.

Do you mean a first in the United States?

Yes, a first in the United States but globally too. Georgia has some exchange programs with European universities, for example, with Oxford University in partnership with the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation. There are a number of centers in Europe, such as the Russia and the Caucasus Regional Research Center at Malmo University in Sweden, or the Caucasian Studies program at the Friedrich-Schiller-Universität at Jena, but none of them are specifically focused on Georgia. The Georgian Studies program at Harvard in that sense is unique; it is not only a first in the US, but in Europe too. Georgian students who are currently studying at Harvard have written to me volunteering their help. I have had letters from scholars all around the world who are interested in collaborating with us. It is something that we, as kartvelologists, needed, and have never had until now.

You mentioned that the program’s establishment at Harvard benefits both Georgia and the United States. What kind of benefits are you referring to?

This center has two core functions – one of them is to enable American citizens to find out more about Georgia, another is to promote research into Georgian society, politics, history, and culture. We will support young and established scholars from both the US and Georgia. We will, in particular, encourage collaboration between Georgian universities and Harvard. One of the things that Georgian scholars need right now is greater integration with Western scholarship. Western scholarship is not going to “teach” Georgians; Georgians have their own great schools in the sciences, in history and linguistics. But at the university level, among undergraduates and graduates, there is work to be done to ensure Georgian scholars can reach the standard expected by Western universities. Georgia is somewhat isolated from Western institutions of Higher Education (though the situation has improved immensely over the last decade), and this affects the competitiveness of young Georgian scholars who are seeking grants and other forms of support. We need to help Georgian scholars compete and offer them greater opportunities to interact with their colleagues in the West, We can do that through our program. We will invite Georgian students and scholars to Harvard, and send Harvard professors to Georgia.

It is essential, particularly now in an environment of so much misinformation, to promote accurate information about Georgia. We want American citizens to have a better understanding of Georgia’s importance to America’s interests abroad. We also need a place where American journalists can come and receive reliable information about your country. We need to develop a public forum where we can talk honestly and objectively about Georgia. Georgia is politically important to the United States. It is still the most promising democracy in the South Caucasus, despite continuing problems. We need to maintain America’s interest in the region and help Georgia as much as we can to strengthen and sustain democratic institutions and ideas.

You have talked a bit about this already, but I would like to ask again – why is the study of Georgia and the South Caucasus critical in improving American geo-political and cultural understanding?

Americans know a little bit about Georgia – they could probably identify Georgia on a map, but they know very little about who Georgians are, or about their history. One of the important goals of our program is to promote cultural outreach. That means cultural events here in the US. We aim bring to Harvard Georgian cultural representatives, such as film directors, writers, and artists. There are some remarkably interesting modern Georgian writers nowadays, such as Aka Morcheladze and Temur Babluani, who need to be translated. We want Americans to know Georgia through its literature, music and art. This is one of the best ways to promote Georgia’s contribution to world history and culture. We will also be providing material on political and international issues, which means talking to important people in Washington. These are all ways to raise political understanding between Washington and Tbilisi. This is not propaganda, God forbid, but it is work designed to enlighten people in Washington about why Georgia is important to US interests abroad.

What does the program include?

A major aspect is research, another is teaching, and a third is outreach. We will provide financial support for visiting scholars from Georgia to come to Harvard. This is particularly important. We want to give Georgian scholars the opportunity to work with their colleagues at Harvard and extend their contacts with other international scholars while they are here. We will collaborate with Georgian higher educational institutions on joint projects, including TSU and Ilia State University, but also with universities in the regions, in Kutaisi and Batumi. Too often the focus is on Tbilisi, and the rest of the country is forgotten. We will establish workshops and seminars on vital topics in Georgia, such as elections, the economy, church-state relations, and minority rights.

A very important part of the program is to train young American scholars who will work on Georgia in the future. We will provide research grants for American students to travel to Georgia and to work there as interns, or as researchers and students attending courses at Georgian universities. We need to create a cadre of young scholars here in the US, who will continue and sustain the work of the Georgian studies program long after I have retired as its first director.

Very important to the work of the Program is teaching the Georgian language. If you intend to study Georgian history or politics, you need to know the language. The idea that you could do all your research on Georgia in Russian or English is no longer viable. You must learn the language. We have a linguistics professor at Harvard, Steven Clancy, who will help us teach Georgian, but we plan to invite Georgian native speakers to help young Harvard scholars learn the language. Now that we have a center, we will be able to attract students from all over the US who are interested in learning the Georgian language.

Who are the people who are leading this program besides you?

I will direct the program, but I have a fabulous team working with me. We will all be based at the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard. The Davis Center covers many diverse regions and populations on the Eurasian continent. It is not just about Russia. Harvard has strong centers which cover Ukraine and Central Asia, but until now, we had nothing for Georgia. Now we do! Rawi Abdelal of the Harvard Business School is the current director of the Davis Center, and Alexandra Vacroux is the Center’s extremely energetic Executive Director. Both of them know Georgia well, and I am working closely with both.

Harvard has one more advantage. It has a wonderful collection of Georgian materials. The archives of the Georgian Democratic Republic, for example, were originally sent to the Houghton Library at Harvard in the 1970s. They were previously housed in Leuville (France), in the “Chateau,” a gathering place for France’s Georgian Diaspora, but they were seriously deteriorating. Harvard archivists treated and preserved the archive and kept microfilm copies after the originals were returned to Georgia. There are many other materials at Harvard in the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library, which are relatively unknown and which we intend to catalogue.

The Georgian Studies program will host an annual academic conference on Georgia and the South Caucasus. What kind of event will this be?

In the fall of 2022, we will have our first international conference. These conferences will be a place to collect together international scholars along with Georgian scholars to discuss themes of interest to us all. We have not decided on the theme of the first conference yet, but have started discussions. An international conference is an important way to generate interest, and to promote collaboration between different scholars. If you can listen to what other scholars have to say, even if their research is critical of current events or policies in Georgia, then will you learn. This is central to Georgia’s democracy. You need an independent judiciary and a free press for a healthy democracy, but also an independent higher educational system that engenders questions and promotes open discussion.