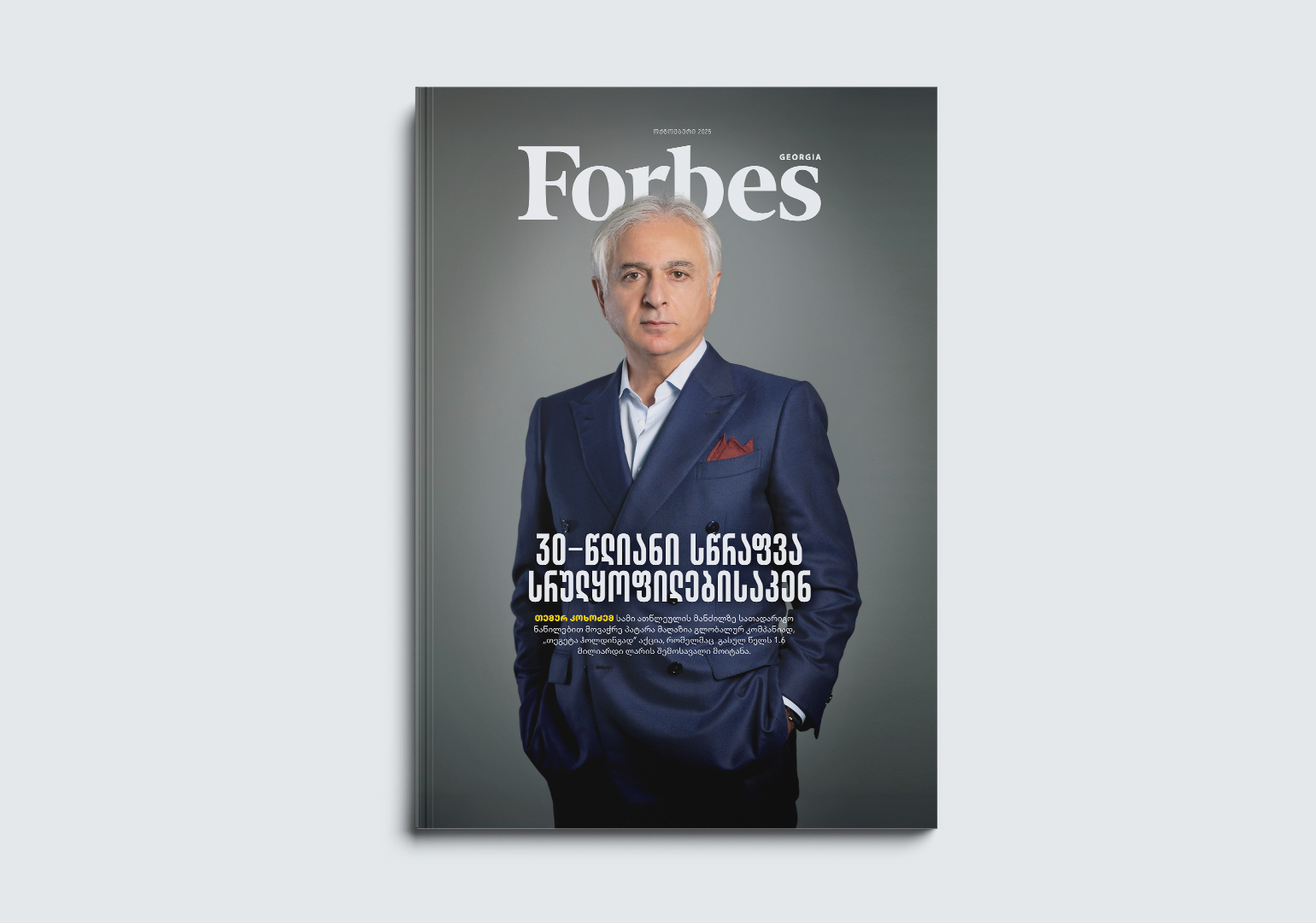

George Ramishvili strides into a nightclub he owns in Batumi, a seaside city of 150,000 in the former Soviet republic of Georgia. It’s a smoky scene inside, with strobe lights flashing, music pulsing, teenagers sweating. Ramishvili, 50, passes through one room and into another, settling at a dining area in the back, where beats still pump through the walls but it’s bright and quiet enough to talk business.

Taking the seat at the head of a long wooden table with two associates, Ramishvili gazes out the window at a stretch of land alongside the Black Sea where, until December, he was planning to build a 47-story Trump Tower. That deal fell apart as Donald Trump ascended to the White House, leaving Ramishvili with 15 acres of undeveloped land and an unprecedented business challenge: What is a foreign tycoon to do when his partner becomes president of the United States, leaving their project in limbo?

His answer underscores one of the great problems of the Trump presidency, one that gets less attention in the face of so many other great problems. In choosing not to divest his assets, Trump has opened himself to the prospect that foreign tycoons will signal that there’s money for him down the road–while in the short term they enrich themselves.

Ramishvili is planning to build a fake Trump Tower.

The fake Trump Tower will sit on the same 15-acre site and use the same Trump-approved design. Timothy Barton, a Texas developer who worked on Trump projects for years, sits with Ramishvili, seemingly ready to dive in. The interior will reflect the same decor Ivanka Trump had envisioned. The Georgian government might name the road near the place after Donald J. Trump–the partners have already discussed the building project with the country’s prime minister. And on this night, in this club, itself a replica of what fake Trump Tower will look like, Ramishvili, Barton and the Georgian’s New York-based business partner, Giorgi Rtskhiladze, focus on coming up with a name that says Trump–without quite saying Trump.

“You have the ‘T,’ ” says Rtskhiladze, who started out as a musician known as King George.”You can use that T.”

Ramishvili reflects: “T Tower,” he says, grinning. “T Tower!”

“That’s it, that’s all you do–everybody will notice it,” says King George, who came up with the idea to bring a Trump Tower to Georgia seven years ago. He adds: “If you call it Tower, and T, then it’s Trump Tower … or the Fifth Avenue Tower. Yes, it’s a little cheesy, but it’s right on.”

Someday, the partners say, they hope to drop the pretense altogether, revive the old licensing agreement and officially call the place Trump Tower, remitting an estimated 12% of all sales to the president’s business for the privilege. “The tower will be ready for the Trump mark,” King George says, “if the Trump mark is ready to come back to the tower.”

All of this raises a whole new set of conflict-of-interest concerns. In January, Trump pledged not to do any foreign deals while in office, but his constellation of current and former partners are all too eager to move forward, potentially forcing the president to make foreign-policy decisions that could affect his financial future–whether he likes it or not. The world’s mini-Trumps are a self-selected lot, and like their North Star, they understand that noise equals profits–realpolitik consequences be damned.

“I don’t even care if [special prosecutor Robert] Mueller comes here,” says King George, who is also working to revive a Trump Tower project in Kazakhstan that he had negotiated after bringing Trump’s personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, there. “They can’t find anything. There is nothing there. I can call it T Tower. Why not? Legally, we have no issues. Media-wise, it’s a genius idea.”

To stoke the problems–and, in turn, the media (yes, including Forbes)–King George says, “I will purposely bring 20 Moscow [residents] from Russia to buy the apartments, okay? And I’m going to leak that Putin bought the apartment actually. It’s going to be great.” (He later says he was joking.) King George claims he speaks to the Trump Organization’s chief counsel, Alan Garten, “almost every week,” although Garten likely doesn’t know the extent of the Georgia partners’ ambitions. “Michael Cohen is going to hate me, and Alan Garten is going to hate me even more.” Neither Cohen nor Garten nor the Trump Organization nor White House representatives responded to numerous requests for comment.

“Congress is going to be talking about it,” King George adds. “Everybody is going to come on and start talking about conflicts. And I love it. We’ll create so many f–king conflicts they’ll get lost.”

Donald Trump’s deal in Georgia began in 2009, not as a political drama but as a simple business trip among acquaintances. King George knew Donald Trump’s ex-wife Ivana Trump socially, and he invited her to Georgia to examine opportunities in the country. Afterward King George had a new thought: “Why go with Ivana Trump when we can try with [Donald’s] Trump Org?”

He returned to the U.S. and reached out to Michael Cohen, whom King George says he also knew from the New York social scene. When Trump got wind of the plan, he was not impressed. “The only Georgia I’m going to is Atlanta,” he said, according to King George.

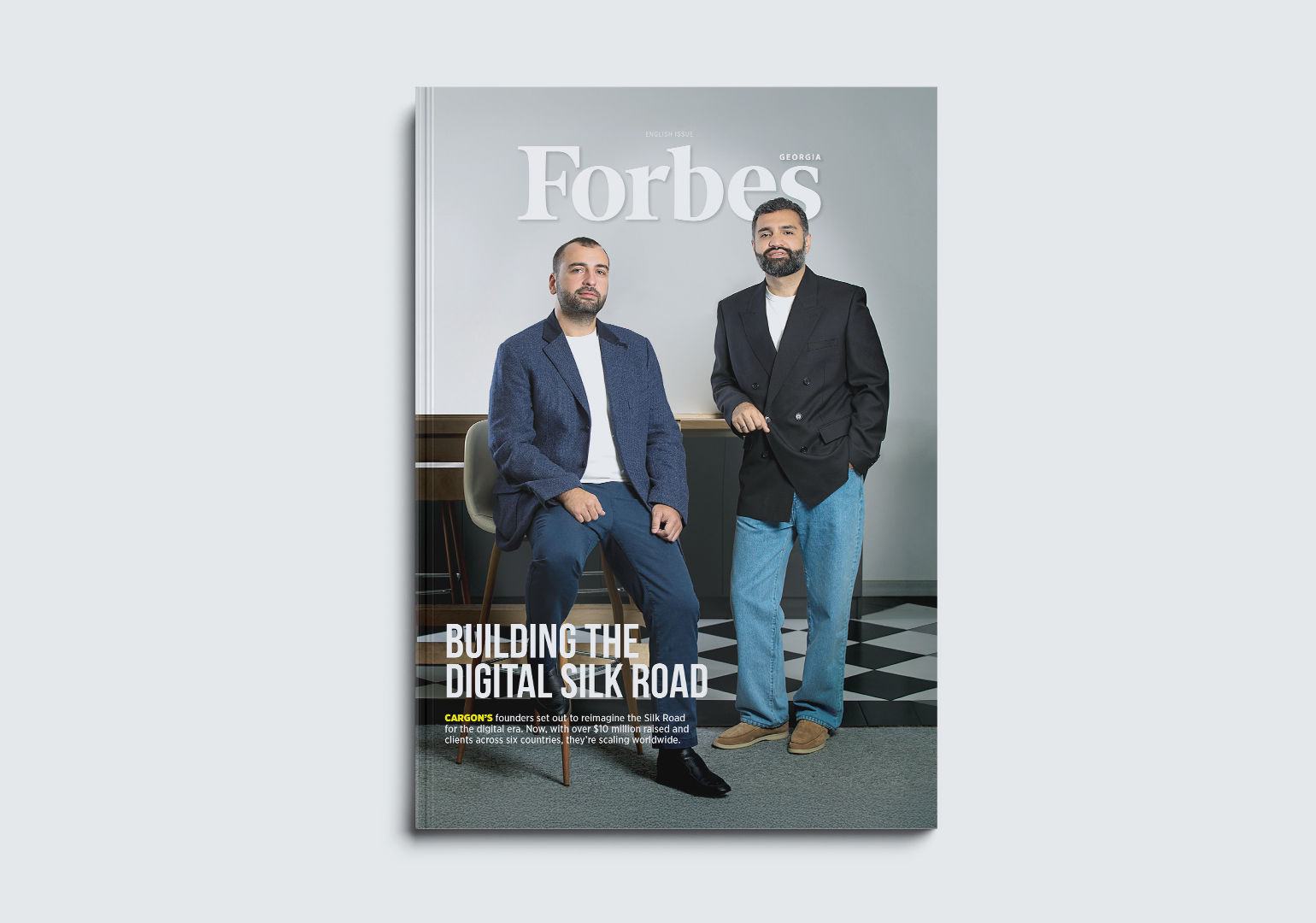

But King George is a hustler. He split his childhood between Moscow and Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi, before arriving in New York in 1991 at age 22 to pursue his music career, which produced one album he describes as “modern-day Genesis.” He proved more capable bridging the U.S. and the post-Soviet Eastern Europe, getting CompUSA computers into Moscow, and Procter & Gamble products and Philip Morris cigarettes into Georgia. Deals like that led to connections, and connections led to investments in banking, media and energy.

To pull off a Trump Tower Georgia, he had to bring in the apparently richer, more influential Ramishvili, who made his bones in energy after the fall of the Soviet Union, transporting oil products from places like Azerbaijan and Chechnya into Georgia and ports on the Black Sea, where they could be shipped off to European markets.

It was a difficult time in Georgia. “There were cases where some businesspeople were killed on the street,” says Eka Gigauri, the executive director of Transparency International Georgia. “It was really not safe to live in Georgia. The system was corrupt.”

With his Silk Road Group, Ramishvili made it through the ’90s, eventually dealing with more colorful characters like the chairman of a Kazakh financial institution who later fled the country under accusations that he had embezzled billions. Ramishvili also increased his presence in Tehran and Russia. In 2004, he was arrested and held in jail for several days, but he never faced any charges. In 2013, the Georgian government launched a money-laundering probe into his company, then dropped the investigation the following year, citing a lack of evidence.

Today he says his businesses contain more than $500 million in diversified Georgian assets and were always clean, which was apparently good enough for the Trump Organization. King George says he arranged a meeting between the New York real estate developer and then-Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili. A year later, in 2011, the Georgians were in business with Trump, forking over an estimated $1 million up front to him, with the real money–a risk-free 12% of all revenue–to come once condos started selling.

But in 2013, Saakashvili left office, and at the same time the Georgian economy slowed down. The Silk Road Group decided to push the project back, leading to an awkward encounter in 2015, before Trump announced his presidential campaign. King George says he was walking down Fifth Avenue in New York when he saw the future president on the street. Evidently embarrassed that the tower was still not under construction, King George tried to hide in the crowd. Trump spotted him anyway. “And Donald goes, ‘Giorgi, don’t let me down!’ ” says King George.

It was ultimately Trump who let Ramishvili and King George down. One month after Trump defeated Hillary Clinton, Trump Organization lawyers called King George to say that they wanted out of the deal, citing concerns, the Georgians recalled, over the emoluments clause of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits federal officials from receiving gifts, payments or “emoluments” from foreign governments. It is not clear why the president, who is facing multiple lawsuits that accuse him of violating the emoluments clause, would be so concerned about it in Georgia but not in the other countries where he does business. King George says it’s possible Trump backed out because of Russia’s hostile relationship with its small southern neighbor, but he thinks it’s more likely that the Trump Organization had concerns about the need for Georgia’s government to approve a site expansion.

King George says he’s not above asking his old–and targeted future–partner for help if the Russians, nearly a decade after their war against Georgia, launch a full invasion. “I think any Georgian would love to get in touch with the White House and the American government to ask for help,” King George says. “And I would do everything possible to find a way.”

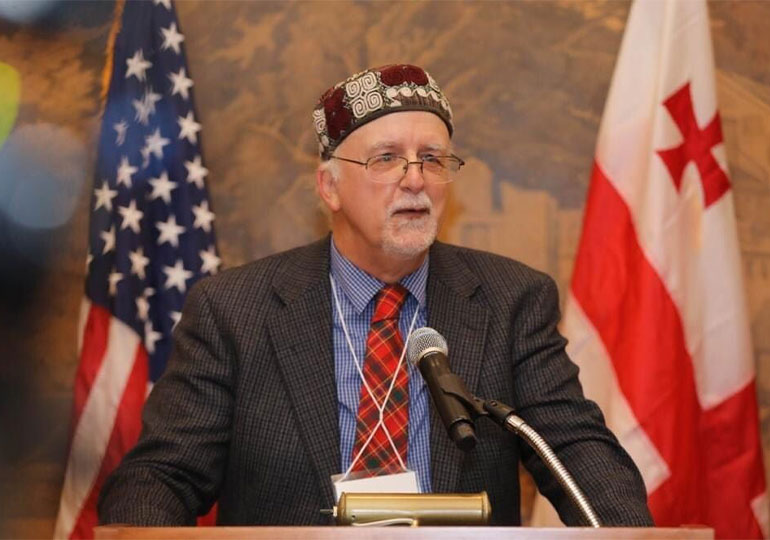

But it’s exactly that sort of high-stakes scenario in which conflicts of interest can be most problematic. “Where would we have been in World War II if Franklin Roosevelt had various side deals going on with Germany?” asks Richard Painter, who served as the chief ethics lawyer for George W. Bush.

That’s a question that can be asked around the world. The Trump Organization maintains partnerships in at least ten countries. And that’s not counting Georgia and Kazakhstan, where the ex-partners feel they have the right to move forward with the projects, at least in spirit, with the president possibly catching up to the deal later.

“We already paid him,” King George says. “They canceled it. Fine. Our joint statement says, ‘I keep these guys in high regards. We love them. They’re great.’ Donald is going to wake up in the morning at the White House and say, ‘This motherf–ker has figured it out.’ That’s what he’s going to say.”

Sitting in the back of a blue-and-white helicopter, Ramishvili stares down at a patchwork of farmland north of the future fake Trump Tower. The fields eventually give way to mountains, and the chopper descends into a remote valley. Ramishvili rushes out, as he’s late to the opening of a sort of religious hotel, hosted by the patriarch of Georgian Orthodoxy, the church’s equivalent to the pope.

Ramishvili’s influence is clear. A priest spots him and waves him through the crowd to the front row, where he stops to greet the Georgian president, prime minister and speaker of the parliament, and then stands next to them. After the patriarch finishes speaking, the priest waves Ramishvili over to be the first to kiss his hand. Ramishvili drops down to one knee while the president, prime minister and speaker of the parliament wait behind him. He exchanges pleasantries with members of the Georgian royal family.

Those sorts of connections come in handy. Ramishvili talks about reshaping Georgian laws in ways that would benefit his business. He hopes to build a casino adjacent to the Trump project, he says, so he pushed the government to limit other casinos in town, extend the length of the licenses to operate casinos and require a certain amount of additional investment, raising the barriers to entry for potential competitors.

It should be noted: Like a presidential tweet that contradicts the previous day’s tweet, King George now denies that Ivana Trump inspired the Donald Trump deal, that Donald Trump was initially dismissive about the Georgian deal, that Trump made that comment to him on the street (“That’s my internal thoughts”) and that he is trying to create a media storm or a conflict of interest, despite having previously said what is closer to the opposite of all of these. For his part, Ramishvili denies trying to influence government policies in his favor.

If President Trump doesn’t eventually play ball, the Georgian duo have brainstormed contingencies. One possibility is bringing Ivana Trump back as a business partner to license her very similar name on the tower. Another is recruiting Trump ally Steve Wynn to help turn the greater site into a gambling hot spot.

Or they could just continue on their current tack, keeping their development legally separate from anyone named Trump while still making money off of a perceived connection to the president. “It might be the best thing that ever happened, canceling this deal,” King George says. “Where else are you going to find a way to utilize the Trump name to market your property? Where? How? How much would it cost you now? To use the Trump name associated with your project, if you had to pay right now, it would probably cost you $50 million, maybe more. You can do it for free.”

And according to Ramishvili, President Trump is watching. In May, the prime minister of Georgia paid an official visit to the White House. He met mostly with Vice President Mike Pence but did get a few minutes in the Oval Office with the president. Ramishvili, who did not witness the exchange, says Trump asked about his former real estate project in Batumi.

While Donald Trump promised not to do any new foreign business deals during his presidency, there does seem to be an active effort to figure out what he’ll do after he leaves the White House. Since Trump started his campaign, his private business has reportedly secured more than 50 additional trademarks in seven countries and extensions on others, including 6 in Russia during 2016, 4 of which were issued on November 8, the day Donald Trump was elected president of the United States.

King George thinks the Georgia deal could serve as a bellwether for Trump’s moneymaking plans after his presidency (or before, if the Trump Organization so chooses). “It’s a deal breaker or a deal maker,” he says. “Once this goes through, all of the opportunities open up.”

Accordingly, he’s not being shy about it. In a move that can only be described as Trumpian, the Georgians have a plan to be in New York in late September to officially announce the construction of fake Trump Tower from inside real Trump Tower.

by Dan Alexander, Forbes.com

Forbes Georgia: სარედაქციო გუნდი