The small nation of Georgia has just announced a locally made reconnaissance and strike drone, known as Project T-31, adding a new dimension to the country’s armed forces. The move is part of a long and at times farcical history of drones in Georgia, one which highlights why even small nations are increasingly building their own.

Georgia, with a population of four million, is in a perilous location: it shares borders with much larger powers Turkey and Russia, as well as Armenia and Azerbaijan whose conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh erupted last year into a bloody war. This concluded with Azerbaijan taking control of disputed territory, and further rounds are possible.

Georgia has substantial Armenian and Azeri minority populations with an obvious risk of any conflict overspilling. Georgia’s offer to mediate in the recent war was rebuffed. No surprise that there are moves to ensure the military is well-prepared. And that means drones: Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drones devastated Armenian forces.

“The Nagorno-Karabakh 2020 war probably had a powerful effect on the Georgian military, with respect to observing what a few UCAVs [unmanned combat air vehicles] that are integrated into a larger tactical picture can do,” Samuel Bendett, an expert on the Russian defense scene, and adviser to both the CNA and CNAS told Forbes.

The propeller-driven T-31, weighing 800 pounds, and carrying four missiles looks like a scaled-down version of the TB-2, itself very much in the mold of the earlier U.S. MQ-1 Predator: a slow, long-endurance craft able to orbit an area for a prolonged period to carry out surveillance and hit any targets that reveal themselves.

Georgia has quite a history in this era. In 2008, their conflict with Russia was one of the first in which drones were deployed on both sides. The problem was that Georgia was flying drones supplied by Israel, and the Israelis apparently sided with Russia.

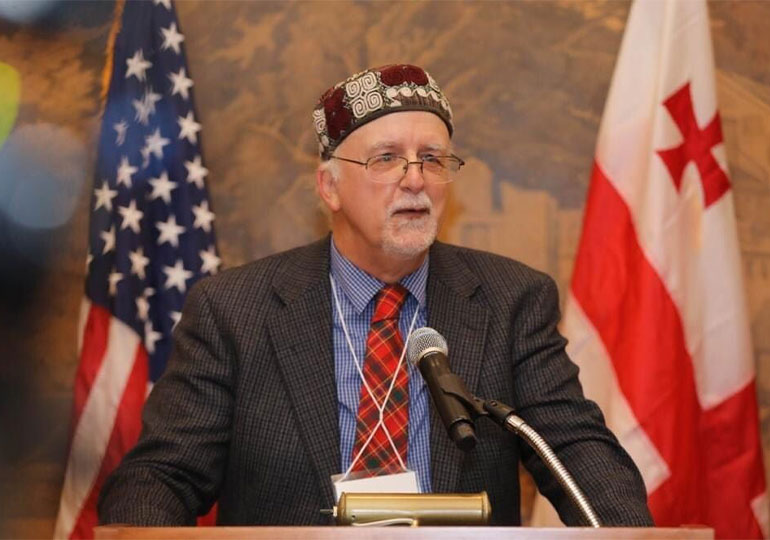

“The codes of those drones, which we bought from Israel, became available to our adversary in very suspicious circumstances and they [drones] were downed,” Mikheil Saakashvili, then President of Georgia stated in 2012.

The exact number of drones (between three and seven) and how they were lost remains disputed. Some have even claimed that using communications data supplied by Israel, the Russians simply hacked into the Georgian drones and crashed them, but this is disputed.

In 2012 Saakashvili, unveiled a new, supposedly locally-made drone which he claimed was superior in some ways to the Israeli models, and that “We no longer depend on others.”

However, sharp-eyed analysts spotted that the reputedly Georgian drone looked remarkably similar to one made in Estonia, and in particular parts of it has a camouflage pattern unique to Estonian armed forces. The ‘Georgian’ drone turned out to be a licensed copy of a model made by Estonia’s ELI Simulations.

In 2015, Georgia announced another locally-made drone, an unmanned helicopter nicknamed ‘Black Widow.’ A mock-up of the craft said to be under development by State Military Technical Center Delta was displayed at Independence Day celebrations, armed with eight rockets and two miniguns. However, nothing appears to have emerged from the ambitious project and STC Delta does not list drone development in their current activities.

In September 2020, Georgia purchased a batch of military drones from the Spanish company Alpha Unmanned Systems. Just one problem: the Israelis gave one of their Alpha 800 drones to Russia, for which the Spanish government demanded an explanation. The Russians may not have gained any militarily useful information – or they may now have a good idea of exactly how to jam Georgia’s new acquisitions.

The use of foreign drones is an issue. It is worth noting that in the U.S., the Pentagon has banned the purchase of Chinese-made DJI drones. They may be very handy, but they are considered a security risk, so the U.S. is trying to encourage locally-made alternatives — not easy, as China totally dominates the small quadcopter marker.

The latest Project T-31 has more than usual urgency for Georgia’s defense; developing the drone may also bring other benefits.

“This domestic product would also help consolidate national know-how and possibly spur on new developments,” says Bendett. “Plus, possible export potential — Georgia does produce advanced aircraft and armored vehicles that it offers for export.”

Technology has advanced considerably in the last five years, and the availability of commercial components means that even backyard engineers can construct crude but effective kamikaze drones like the ones used in Syria. A company like Tbilisi Aviation Enterprise, which is building the T-31, should be able to produce something far more sophisticated.

“The advanced weapons’ research, development, and experimentation space are rapidly expanding past leading industrial nations to the point that small nations like Georgia can have enough technological potential to attempt a project of that magnitude,” says Bendett. “The development and acquisition of different drone classes by former Soviet nations will become a commonplace development.”

If Georgia can make an attack drone, anyone can — Armenia and Azerbaijan are also producing their own armed drones, and proliferation already looks like a done deal. What we do not yet know is how it will change warfare.